One cold night in 1956, the minister of the Burton Street Baptist Church, Sydney, noticed the shadowy outline of a crouched man, oblivious to his presence, writing on the footpath.

‘Are you Mr Eternity?’ asked Mr Thompson.

‘Guilty your honour!’ came the softly spoken reply as the small man stood up. After 26 years of speculation, the mystery of Mr Eternity had been solved.

There, in the gloom, stood Arthur Stace, 160 cm tall, weighing just 50 kg, dressed in a suit and a felt hat. As it happened, Arthur was the church cleaner and very much involved in church life. But no one thought for a moment that he was the mysterious Mr Eternity who, for almost thirty years, had inscribed in chalk the one word ‘Eternity’ almost 500,000 times on the footpaths of suburban Sydney.

One word

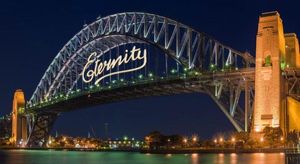

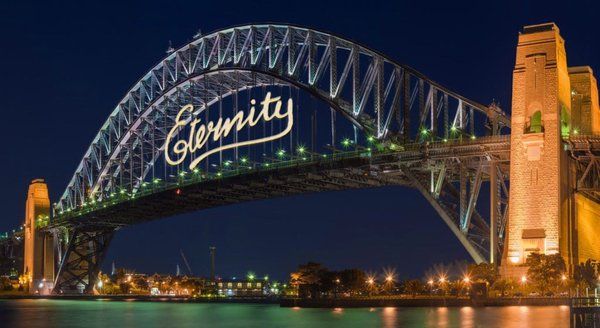

Just after midnight on 1 January 2000, as the most colourful and expensive firework display ever seen over Sydney Harbour drew to a close, the one word ‘Eternity’ appeared in perfect copperplate on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

I feel sure that few of the local audience of over a million Sydneysiders, or of the billions glued to their TV sets worldwide, had any idea of the significance of that one word.

The display was the finest ever. The organisers used the Harbour Bridge, the Opera House, barges, and tall buildings to ensure that the fireworks reached great heights. One rocket rose to four hundred metres before it burst in a mass of colour. It was a great night, but many asked the question, ‘What is the significance of “Eternity”?’ In all the public celebrations I saw, this was the only thing that, for a moment, introduced a spiritual thought.

A bad start

The story behind ‘Mr Eternity’ is a monument to the grace of God who saved a poor sinner from a life of degradation and gave him a lifelong work; to remind the citizens of Sydney about eternity.

Arthur Stace was born in 1884 in the tough, working-class Sydney suburb of Balmain. Arthur, his two sisters, and two brothers frequently slept on old bags under the family house to escape the brutality of their drunken parents.

The children survived by stealing milk and bread from the doorsteps of local homes. They also rummaged through garbage bins to find scraps of food in order to live.

Arthur had little education and was largely illiterate. He became a ward of the State at twelve, and started work in a nearby coal mine at fourteen. Early in life he also began to travel the alcoholic road. This led to theft to support his drinking habit and, eventually, jail at the age of fifteen.

Arthur’s sisters ran local brothels and he earned money by supplying them with grog from the local pubs. Later he said of those days, ‘I was always drunk; always broke; a derelict; a no-hoper’.

Rock cakes and tea

In 1914 he enlisted in the army and served in France and elsewhere as a stretcher-bearer and combat soldier.

But 1918 saw him back in Sydney taking up where he had left off. During the depression years Arthur, like many others, was out of work and depended on the goodness of others to survive. He wanted to give up the drink, but despite repeatedly signing the pledge, he realised he didn’t have the power to do so.

On 6 August 1930, with other ‘down and outs’ he went to St Barnabas Church, Sydney, where, before they were given free rock-cakes and tea, he heard Archdeacon R. Hammond preach. He noticed the difference between his poorly dressed mates and the Christians attending the service. He said to one of his friends, ‘Look at them and look at us. I’m going to have a go at what they have got’.

With that he bowed down and prayed what was probably the first prayer ever to come from his lips. Later he testified: ‘I went to get a cup of tea and a rock-cake, but I met the Rock of ages’.

Shouting eternity

Arthur made his way to a nearby park where, under an old fig tree, tears flowed as he cried, ‘God be merciful to me, a sinner’. God heard his prayer. Arthur found the power to give up alcohol. He found a job which gave him some self-respect.

Later, in November 1932, he attended Burton Street Baptist Church, Darlinghurst, where he heard the ‘brimstone and hellfire’ preacher Rev. John Ridley.

Among other things, Mr Ridley said he wished he could ‘shout eternity through the streets of Sydney’, warning sinners to prepare for their certain meeting with God. In a loud voice he cried out, ‘Eternity! Eternity! I wish I could sound or shout that word to everyone in the streets of Sydney. Eternity! you have got to meet it. Where will you spend eternity?’

Arthur was moved by the Spirit of Christ to take up that call. Although nearly illiterate, he found he could write ‘Eternity’ in perfect copperplate writing.

Newspaper reports

His wife Pearl encouraged him, and most mornings he rose at 4.00 a.m. for an hour of prayer before leaving for the streets of Sydney’s suburbs to write ‘Eternity’ every hundred yards or so. He said that during the night the Lord revealed to him where he should go each morning.

Strictly speaking, it was against the law to write on the footpath, and he was almost arrested on many occasions. But he went about his task claiming, ‘I had permission from a higher source’.

In his early days of writing, some humorist changed ‘eternity’ to ‘maternity’, but this only lasted till Arthur began using a large capital E for his word.

Soon newspapers began to carry reports of the mysterious ‘Mr Eternity’. But although several people ‘confessed’ to the police and newspapers, no one really knew who was responsible.

Suitcase full of tracts

Arthur began to hold street gospel meetings on the corner of Bathurst and George Streets, Sydney, standing on the gutter and preaching the simple gospel of repentance and saving faith in the Lord Jesus. Later he reached a larger audience when he obtained a van and some loudspeaker equipment.

When his identity finally became known, Arthur’s workmates remembered how he would leave them at lunch-time, carrying a suitcase. It transpired that the suitcase was filled with tracts. Arthur spent his lunch-hour walking the streets handing out tracts and encouraging the ‘down and outs’ to look to Christ for power to overcome their addiction.

Today the word ‘Eternity’ is to be found in brass near the Sydney Opera House. This is the only memorial to Mr Eternity, despite efforts to have others erected.

However, the story is told that the GPO clock bell has ‘Eternity’ inscribed on the inside. The bell-tower was demolished during the war and in 1965 it was being reconstructed. The bell was left hoisted in the air for just one night before being lifted into place. In the morning the foreman found ‘Eternity’ inscribed inside the bell.

Arthur suffered a stroke and died on 30 June 1967 aged 83. He left his body to Sydney University and directed that the payment be given to a charity. Several years later his body was laid to rest and hundreds of citizens paid their respects to this humble servant of Christ.

Eternity in our hearts

We can only wonder what moved those who organised Sydney’s firework display to pay respects to Arthur Stace, a saint unknown to this generation, by displaying the word Eternity for millions to see.

Today, occasionally, Eternity is found written on the streets of Sydney or another Australian city or town. But there will never be another Arthur Stace, a converted thief and drunkard, called by our God to bear witness to his saving grace through the Lord Jesus Christ, in this unusual way.

How many lives were touched by the witness of this unassuming saint? Only eternity will reveal how God used Arthur Stace and his one-word evangelistic message. ‘He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also he has put Eternity in their hearts’ (Ecclesiastes 3:11).