The promise of a new start

It might seem inappropriate to ask, but it is not meant to be rude or politically incorrect. When I ask, ‘Whose child are you?’ I am raising the issue of where we belong in a spiritual sense. Recent years have witnessed a general reawakening to human ‘spirituality’; to the fact that, whatever we are as human beings, we are spiritual beings with spiritual needs. The question is, where and how can those needs be met?

Put it this way. Many of us, at some time in our lives, have learned the ‘Lord’s Prayer’. This is the prayer Jesus taught and which begins, ‘Our Father, who art in heaven’. But have we ever stopped to ask ourselves, ‘But is he our Father?’ Do the words actually mean anything for us, or are they just hypocritical ramblings?

On the spot

Jesus himself put a group of people on the spot over this very issue almost two thousand years ago. He turned to a group of religious people who thought they were his followers. He questioned them about the spiritual family to which they thought they belonged. Whose children were they? The answer they gave was quite telling.

They said they belonged to Abraham’s family. In other words, they thought that their ethnic links to a man who was called ‘the friend of God’, and their membership of the nation which descended from him, were sufficient to make them God’s children. Jesus told them an altogether different story. Without mincing his words, he said, ‘You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desire’ (John 8:44).

Jesus’ blunt words should not be misconstrued as harsh. He knew that before God could really become their Father, and change their lives, these people had to make a painful discovery about themselves. The same thing is true for people of every generation and regardless of their nationality.

False security

The false sense of security displayed by these people in Jesus’ time is not unlike that found in people today. Britain is still regarded, at least in some vague sense, as a Christian country. Thus many people equate being British with being Christian.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Whatever our ethnic or religious background, no one can claim to be born into God’s family as of right. Like those to whom Jesus spoke, we are all by nature children of a different, darker family.

The sad reality of this is seen in the ‘family traits’ displayed by all mankind. No one nation has a monopoly on evil; be it lying, stealing, cheating, or whatever. The same evil characteristics are found the world over, and they can all be traced to the same source in terms of the ‘genetics of the soul’.

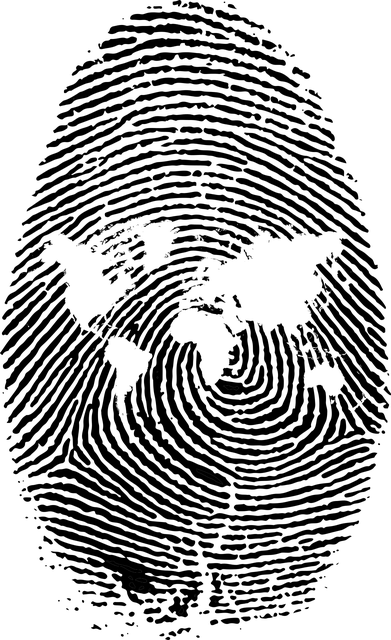

It is as though the whole human race shares a spiritual genetic finger-print of evil. Nobody has to be taught to do wrong. It just comes naturally, and all our valiant attempts at self-improvement come to nothing.

Receiving Christ

Does this mean there is no hope for anyone? Are we all doomed to an endless downward spiral, in this world and the next? Or is there a possibility of change?

Jesus says there is. He told the same group of misguided people that to belong to God’s family, they must love him (John 8:42). They must recognise him to be God’s own Son, who had come into the world to save people and bring them back to God. They must trust him and follow him.

Elsewhere in the Bible it says, ‘To all who received him, to those who believed in his name, he gave the right to become the children of God’ (John 1:12). Those who have been given this right are said to have received ‘the Spirit of Sonship’ the Spirit of God himself. It is the Spirit who gives new life to our soul and enables us to call God ‘Father’ and mean it (Romans 8:15).

In other words, the good news we find in the Bible is the promise of a new start in life for all who come to trust in Jesus. He alone can blot out their shameful past and give them the new life shared by all the members of God’s family, a life that allows them to be different. He promises hope, not just in the world we belong to now, but also in the world which lies beyond and after death.

Our spiritual parentage is an important issue even more important than the human family or ethnic group we happen to belong to. The issue has eternal implications. It must leave each one of us asking, ‘Whose child am I?’