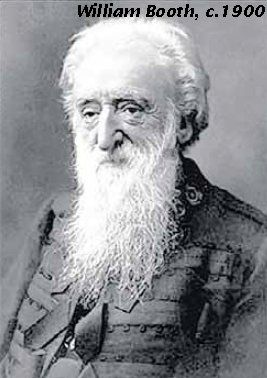

Part 1 is here: William Booth (1829-1912)

William Booth (2)

In 1861 William and Catherine campaigned at Hayle, St Ives, Redruth and Camborne in Cornwall. Strong men shouted out, fearing hell, and in sorrow for their sins. An evil spirit troubled a woman who appeared to talk to her dead husband.

The disorder disturbed William Booth, who told them to pray and sing when he commanded. Although about 7000 souls were recorded as saved, the local Methodists eventually banned the Booths from their pulpits.

Itineration

Local fishermen there had contacts in Cardiff, so that is where they headed after Penzance, in 1862.Their first meetings were at a Baptist church.

William soon received support from some wealthy evangelicals — the Cory brothers John and Richard who were colliery- and ship-owners, and Jonathan E. Billups, a railway builder. In 1863 their meetings were held in a circus tent. Soon the moral tone of Cardiff changed for the better and the magistrates had little to do.

Their next visit was to Walsall in the West Midlands. The outcasts of society refused to enter chapels, so William employed the new tactic of marching through streets in slum areas, leading the people to wagons where they were addressed by converted prize-fighters and thieves — the Hallelujah Band.

The Booths then journeyed to Leeds, where their sixth child, Marian Billups Booth, was born. Catherine was reduced to pawning her jewellery and lecturing on temperance to gain support. William preached at Nottingham and Sheffield, but the churches there offered him little encouragement.

Catherine received an invitation from Free Church Methodists in Rotherhithe to lead a mission. Handbills advertised ‘Come and hear a woman preach’, such was the novelty. Modestly dressed in black, she had a quiet manner and a calm and precise delivery.

Catherine felt at home in London, so they moved back to a rented house in Hammersmith, and then on to Hackney. William Booth conducted his first London mission in the East End, on Sunday 2 July 1865, in a rented tent on the Quaker burial ground.

After six years work, they eventually moved to a large market hall in Whitechapel Road, and after nine years of lay preaching William broke with Methodism to become an independent evangelist.

Salvation Army

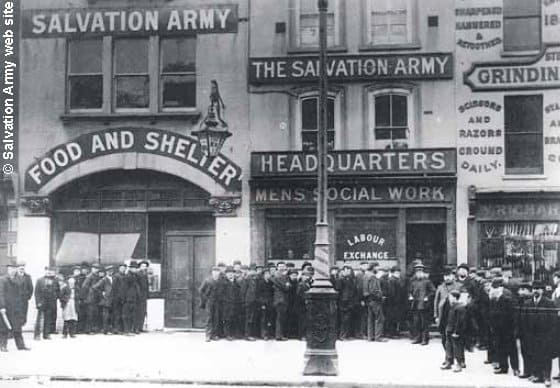

Booth found his followers reluctant to enter a church building. Furthermore, respectable church members were unhappy to sit near flea-ridden urchins. So Booth formed ‘an organisation entirely outside every Christian church in order to accomplish my object’.

Booth formed the East London Christian Revival Society, which later became the East London Christian Mission. Looking ahead to a countrywide outreach, he held the inaugural conference of the renamed ‘Christian Mission’ in November 1870.

The Mission’s foundation deed gave William absolute authority as general superintendent to confirm or set aside any of its decisions; its constitution allowed gifted women to be eligible for any office including preaching, and to speak and vote at official meetings.

Whitechapel Hall was now crowded, with up to 1200 people, and a soup kitchen was opened serving up to 1000 people per day at 2 pence per bowl. Booth argued that ‘it is primarily and mainly for the sake of saving the soul that I seek the salvation of the body’.

George Scott Railton joined the Christian Mission in 1873 and became Booth’s secretary. In 1876, at Railton’s suggestion and on the basis of 1 Thessalonians 5:23 — ‘And the very God of peace sanctify you wholly; and I pray God your whole spirit and soul and body be preserved blameless unto the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ’ — ‘entire sanctification’ was written into the Mission’s articles of faith.

A draft annual report of the Mission described themselves as a ‘Volunteer Army’. Bramwell Booth objected that he was no volunteer; he had been called by God. His father walked over to Railton’s desk, crossed out ‘Volunteer’ and substituted ‘Salvation’.

So, in 1878, the Christian Mission became the Salvation Army and a new era had begun. From now on, everything was expressed in military terms. Prayer was called ‘knee drill’ and giving an offering ‘firing a cartridge’.

A uniform was introduced and a banner designed. Brass bands were introduced, both to attract people to join them as they marched to the ‘citadels’ (churches) and to distract troublemakers. They set hymns to music-hall tunes so that people could join in singing immediately.

Growth

It was a band passing the entrance to a theatre as Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones was coming out that convinced Lloyd-Jones he should choose to stand with God’s people rather than seek the kudos of an illustrious career in medicine.

C. H. Spurgeon did not approve of Booth’s ‘playing at soldiers’, but this was no game. The calls for temperance at every meeting angered the brewers, landlords and pimps, who employed rent-a-mob tactics, forming their own ‘skeleton armies’ equipped with sticks, burning coals, stones, dirt and garbage, and waving a black skull-and-crossbones flag.

In 1884 there was a riot at Worthing; and at Hastings Susannah Beattie was stoned and kicked to death. But the Salvation Army stood their ground. By the end of the decade, there were no major attacks on it and their social work had gained public sympathy.

In 1890, Thomas Huxley (‘Darwin’s bulldog’) attacked William Booth in an article in the Times. Booth was accused of religious fanaticism, prostitution of the mind and exacting blind obedience to unlimited authority. This was payback time for Booth’s deriding of Darwin’s theory of evolution, which Huxley had embraced.

In spite of the opposition, numbers grew, and by the end of 1890 the Salvation Army had 2874 corps, 896 outposts and 9416 officers. The weekly magazine, the War Cry, was launched in 1879, and by 1890 had a weekly circulation of 300,000, with a worldwide total of 37,400,000 publications in 15 languages.

The War Cry was taken around public houses by ‘hallelujah lasses’, women officers originally appointed for children’s work, but also engaging in evangelism. These women were sent all over the country with little financial support. They often relied on charitable offers of food to survive and encountered much ribaldry in open air work, but they stuck to their guns.

Darkest England

In 1890, William Booth published In darkest England and the way out. He identified ‘the submerged tenth’ of the population who had little hope of escaping poverty or vice. They included the starving, drunkards, paupers, unemployed, homeless, criminals, prostitutes, sick, lost and suicidal.

Booth proposed many avenues of social assistance, saying people have to be ‘rescued from hell here and hell hereafter’. He set up 954 institutions, including ‘city industrial workshops’ for carpentry, mat-making, shoe-repairing, etc. He was careful not to run sweatshops for match-making.

He paid more than the going rate and sold at current prices, so as not to undercut other traders. He used red phosphorus to prevent his workers getting ‘phossy jaw’ through using white phosphorus. Those lacking craft skills lived on self-sufficient agricultural cooperatives. One such establishment survives at Hadleigh (www.hadleighfarm.co.uk).

Teams would collect unwanted food and household items from wealthier districts and recycle them for the benefit of the poor. Booth helped released prisoners; and established a poor man’s bank and rescue homes for women enslaved in the sex trade. By 1890, 3000 women in Britain had been helped in 13 homes, and 17 such homes had been established abroad.

In all these social ministries, Booth remained convinced of the need for spiritual rebirth. He said: ‘Spiritual life is divine in its origin. It is a creation of the Holy Spirit. Jesus Christ was at great trouble to teach it. “Marvel not”, he said, “Ye must be born again”.

‘You must insist on it in your people. The only way to secure conduct of a lasting nature is by affecting a change in that nature. Make them new creatures in Christ Jesus and you will have a Christ-like life’.

Honour

William Booth travelled the world, led prayers at the US Senate and met Presidents McKinley and Roosevelt. He was made an honorary Doctor of Civil Laws by Oxford University and given freedom of the cities of Nottingham and London. In June1904, he had an audience with King Edward VII.

Aged 75, he travelled 1224 miles from Land’s End to Dundee, addressing 164 meetings. In succeeding years, he visited Israel and Australia, and lectured in Rome.

He visited Holland, aged 83, but he was losing his sight. Eye operations proved unsuccessful and, on 20 October 1912, he died.

65,000 mourners filed past his coffin and 5000 marched behind the cortège. There were wreathes from the King and Queen and a dozen heads of state. William Booth was buried next to Catherine in Abney Park cemetery, with his cap and Bible on his coffin.

The challenge remains: how do we reach out compassionately with the gospel to those who never enter our church buildings today?

Nigel Faithfull

The author’s first article on William Booth was published in the September ET and can be read online here: William Booth (1829-1912)