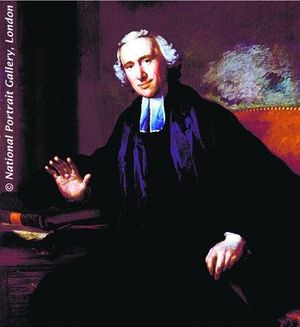

‘Old’ Hartlepool is a small port situated five miles north of the River Tees. Here, three hundred years ago, on 25 September 1714, William Romaine was born. He was to become a man of great intellectual and spiritual distinction.

His grandfather, Robert, had fled France in 1681, taking advantage of the relaxation of immigration laws in favour of French refugees (Huguenots) at the time that their liberty was threatened during the rule of Louis XIV.

Robert arrived in England with his young family and become a distinguished citizen of Hartlepool. His son William served as town mayor on three occasions. His marriage to the godly Isabella produced a family of nine children, of whom William was the second.

Early life

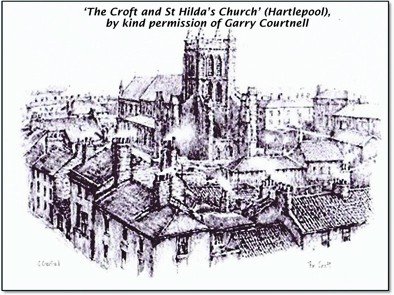

Young William was nurtured in a disciplined home and church environment. The family attended the parish church of St Hilda, which still dominates the town’s skyline.

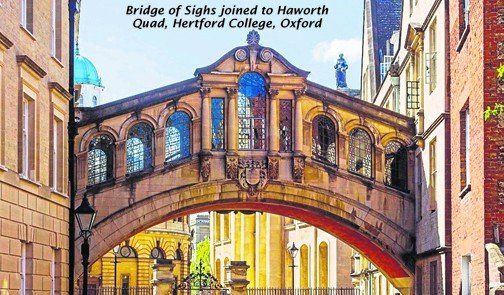

At the age of 10, William was sent to Kepier Grammar School, at Houghton-le-Spring, founded in the mid-sixteenth century by ‘apostle of the north’ Bernard Gilpin. He proceeded to Hart Hall (later Hertford College), Oxford. Later he moved to Christ Church College, where Charles Wesley had become a tutor.

As in the case of George Whitefield, he attended as a servitor, obtaining free tuition for performing menial tasks for the university and its more affluent students.

Though a contemporary of the Wesleys, Whitefield, Hervey and other members of ‘the Holy Club’, he did not attend their meetings but concentrated exclusively on his academic studies.

A visitor to his college observed Romaine walking past dressed in a rather slovenly way and asked the Master of the college who the man was. The Master replied, ‘That slovenly person, as you call him, is one of the greatest geniuses of the age and is likely to become one of the greatest men of the kingdom’.

Though a somewhat exaggerated assessment, Romaine left Oxford as a scholar of rich academic promise. In particular, he became a fine Hebrew scholar.

Spiritual awakening

Romaine was ordained by the Bishop of Hereford (1734) after receiving his BA. He had a brief curacy at Lewtrenchard (Devon), before returning to Oxford to proceed to his MA (1737).

In December 1738, he was ordained ‘priest’ by Benjamin Hoadley, Bishop of Winchester, and became curate to John Edwards at Banstead (Surrey). In 1739 he preached a sermon at St Mary’s (Oxford University), in which he refuted William Warburton’s view that the writings of Moses contain no clear doctrine of life after death. His critics claimed he did so in a manner which was arrogant and displayed a lack of charity.

At Banstead he met Daniel Lambert, elected Lord Mayor of London (1741), who invited the young curate to be his chaplain. Between 1740 and 1745, Romaine produced a new edition of the Hebrew dictionary and concordance of Marios de Calasio (4 volumes). In connection with this work, he took up residence in London to be near the printers.

In a letter (1766) Romaine described his spiritual state prior to 1745. Writing in the third person, he says of himself, ‘He was a very vain, proud man, who knew almost everything but himself, and therefore was very fond of himself. He met with many disappointments to his pride, which only made him prouder, till the Lord was pleased to let him see the plague of his own heart.

‘He tried every method that can be tried to find peace, but found none. In his despair of all things else, he betook himself to Jesus and was most kindly received’. His entry into new life probably occurred in 1745.

London ministry

At this stage we may judge Romaine to be a very competent Hebrew scholar in whom ‘the fire of God’ was beginning to burn. God in his providence was preparing Romaine to be the leader of Evangelicalism in London. However, for a while, that objective was in doubt, due to his frustration in failing to obtain any settled situation in the capital.

In autumn 1748, Romaine had resolved to leave London for the north east of England. His baggage was on a ship and he was preparing to embark when, in the providence of God, he was met by a stranger who was a friend of his father and who offered to help him secure the vacant lectureship at St Botolph’s, Billingsgate.

Having served in this position for 11 months, Romaine resigned to take a similar post at St Dunstan-in-the-West (near Fleet Street). There, he preached every week for the rest of his life, giving expositions of every book in the Bible at least once.

In June 1751 Romaine became, for 10 months, professor of astronomy at Gresham College, in addition to his preaching duties elsewhere. He openly opposed Newtonian physics, the general methodology of astronomers, and even the instruments they used.

He was criticised for introducing spiritual remarks into formal lectures. However, the main criticism of his tenure, which precipitated his resignation, was that ‘he attracted the wrong sort of persons’.

In 1752–53 Romaine became nationally known for opposing a bill before Parliament relating to ‘the naturalisation of those professing the Jewish religion’. He produced an opposing pamphlet and preached a sermon in which he took the ill-chosen text, ‘These people being Jews do exceedingly trouble our city’ (Acts 16:20).

Neither the Wesleys nor Whitefield took any part in the controversy surrounding the bill. In great concern George Whitefield wrote: ‘God keep him from further entanglements from worldly policy and fleshly wisdom, which I think have nothing to do with the work of the Lord’.

Widening circle

Prior to his settled ministry at St Anne’s, Blackfriars, Romaine’s eloquent and powerful preaching at St George’s, Hanover Square, attracted a large congregation. Of his preaching there and at St Dunstan’s, Charles Wesley wrote: ‘The Lord of the harvest is thrusting out labourers. Mr Romaine is much blessed’.

In February 1755 Romaine married Mary Price, whom William Grimshaw described as a ‘precious soul’. They had two sons, William who became an Anglican minister and Adam who died in Trincomalee (1782), and also a daughter who died in infancy.

In the summer of the same year, events occurred which precipitated his resignation after five years of faithful preaching at St George’s. Complaints were made to the rector that seats for local householders were taken by ‘low class’ visitors.

Romaine began attending meetings that included George Whitefield, James Hervey and such influential Baptists as Drs John Gill and Andrew Gifford. Their joint influence encouraged Martin Madan to give up his legal career to enter the Christian ministry as chaplain of Lock Hospital. The hospital’s chapel became a scene of powerful preaching, with Romaine making a major contribution.

Romaine was deeply burdened for his country when the seven-year war with France commenced in 1756. He organised a weekly prayer time, which continued as an occasion of intercession for the Church of England. His publication, An earnest invitation, was described by Ryle as one of Romaine’s most useful writings.

One of those to respond to his publication and appeal for prayer was John Newton, who expressed then and later a deep appreciation of Romaine’s ministry and leadership.

In 1764, Romaine’s name was put forward by Lady Huntingdon for the living of St Anne’s, Blackfriars, and St Andrews-by-the-Wardrobe. He preached before the parishioners on 2 Corinthians 4:5. However, ecclesiastical politics complicated matters and this prolonged his election which was disputed in the courts.

Meanwhile, Romaine continued to preach in Lady Huntingdon’s chapels in Sussex. From America (through Whitefield) he received an offer to be minister of St Paul’s Episcopal Church, Philadelphia. This he declined.

Evangelical leader

In January 1768, eighteen months after he first preached at St Anne’s, Lord Henley gave his decision in Romaine’s favour. He had served more than 30 years in the Church of England without a benefice. Now London had a leading Evangelical in his own church.

Romaine urged all Evangelicals to join with him in praying for revival in the Anglican Church. He invited ministerial brethren as preachers, including Augustus Toplady. However, unlike Toplady, he took no part in the Calvinist/Arminian debate, despite being a convinced Calvinist.

The size of the congregation at St Anne’s made it necessary to erect a gallery in 1774. A year later Romaine produced an Essay on psalmody, which was a defence of the exclusive use of psalms in church services.

While he appreciated the hymns of Watts (and quoted them in his sermons), he used only psalms on the Lord’s Day. In this he differed from John Newton, Augustus Toplady, and Lady Huntingdon, who regretted the publication.

As a mature minister Romaine avoided national controversies, including that surrounding the American War of Independence, which commenced in 1775. However, he continued to urge believers to pray for church and state.

In January 1780, John Newton moved from Olney to St Mary, Woolnoth, in the heart of London, and so London now had two beneficed Evangelical Anglican ministers. Even in his 70s Romaine continued to preach four or five times a week at the parish church and at St Dunstan’s.

A long-standing friendship with Thomas Haweis encouraged Romaine to help Haweis begin missionary work in the South Sea Islands, under the aegis of the fledgling London Missionary Society. Romaine urged support for the work from those within his sphere of influence.

Life, walk and triumph of faith

Romaine’s three-part treatise on faith, The life, walk and triumph of faith, written between 1764 and his final year, is, in this writer’s opinion, undoubtedly his greatest legacy to the church and the main reason why he should be remembered.

It is written in a pastoral style, with periodic prayers for the reader. Romaine is determined that readers lay hold of the righteousness of Christ and trust in his atoning death alone for their salvation.

Believers are exhorted to continue in that trust and not turn to legalism and their own righteousness. The accusation of John Wesley and others that the volumes were written in an antinomian spirit is unfounded. Romaine had a high view of the moral law, as reflecting the holiness, justice and glory of the Lord.

He recognised the law is ‘a tutor to lead to Christ’ and that it is the believer’s duty to be thoroughly familiar with the Scriptures, as a mark of love for Christ and an ongoing guide to discipleship.

The Christian life is a walk of faith, centred on the Son of God who ‘loved us and gave himself for us’. Such a walk will bring the believer to a triumphant end, irrespective of the circumstances faced. Those weak in the faith he exhorts to hold to the promises of God and use them as the basis for their prayers.

Romaine had a beautifully balanced understanding of the doctrines of grace and he implicitly rejected Arminianism. He completely dismissed perfectionism as ‘a doctrine which detracts from the glory of God and sanctification by free grace’. Each part of his treatise is self-abasing and God-glorifying.

Final days

Romaine’s final Sunday sermons were preached on 31 May 1795, at St Anne’s, Blackfriars (1 John 1:7), and at St Dunstan’s (2 Corinthians 13:14). Later he preached at St Dunstan’s on 4 June (John 18). Shortly after this he became ill. He died in the early hours of 26 July 1795, full of faith in his Saviour.

His funeral, conducted by his curate William Goode (who became his successor), took place on 3 August at Blackfriars. A large crowd followed the funeral procession.

Six funeral sermons were printed by friends, including one by his close ministerial colleague, John Newton: ‘Mr Romaine was 58 years in the ministry. An honourable and useful man, as inflexible as an iron pillar in publishing the truth and unmoved either by the smiles or frowns of the world. He was the most popular man of the Evangelical party since Mr Whitefield. Few remaining will be more missed’.

Finally, I quote this moving tribute to William Romaine by Bishop Ryle: ‘He stood alone with almost no backers, supporters or fellow labourers. He stood in the same place constantly preaching to the same hearers and was not able, like Whitefield, Wesley, Grimshaw and other itinerant brethren, to preach old sermons.

‘He witnessed to truths which were most unpopular and brought upon him opposition, persecution and scorn. He stood in a public post, continually observed by unfriendly eyes, ready to detect faults in a moment if he committed them. Yet during all these years he maintained a blameless character, firmly held to his principles to the last and died at length like a good soldier at his post’.

John A Crosby was formerly a senior lecturer in physical science at Carlisle College and pastor of Grace Evangelical Church, Carlisle. He now serves as an elder in that church.